The night my mother passed seems like a nightmare that I can’t quite shake.

I know it happened; I know I was there, alone by her side as they undid her IV meds and hooked up the morphine. She was so ready by that time; it was like a laboring mother being given an epidural. She wasn’t afraid or sad really, just tired. Very, very tired. She joked to me as they connected her IV to the morphine line, “Natalie, what time is it?” It’s 8:05, Mom. “Just you watch. By eight-oh-ten I’ll be gone.” I smiled and cried and held her hand. I didn’t want her last memories on earth to be bad. At that moment I just wanted for her what she wanted, relief and happiness. And I have to believe that 11 hours later, when she passed, she finally got it.

And at that moment when she took her last eerie, raspy breath, I was left here alone. Alone to figure out what’s next, what’s left. And although it’s been a year already, I’m not sure I’m any closer to figuring anything out. I still find myself making mental notes to “tell Mom” about this or that, asking her questions out loud, experiencing overwhelming sadness at the oddest moments.

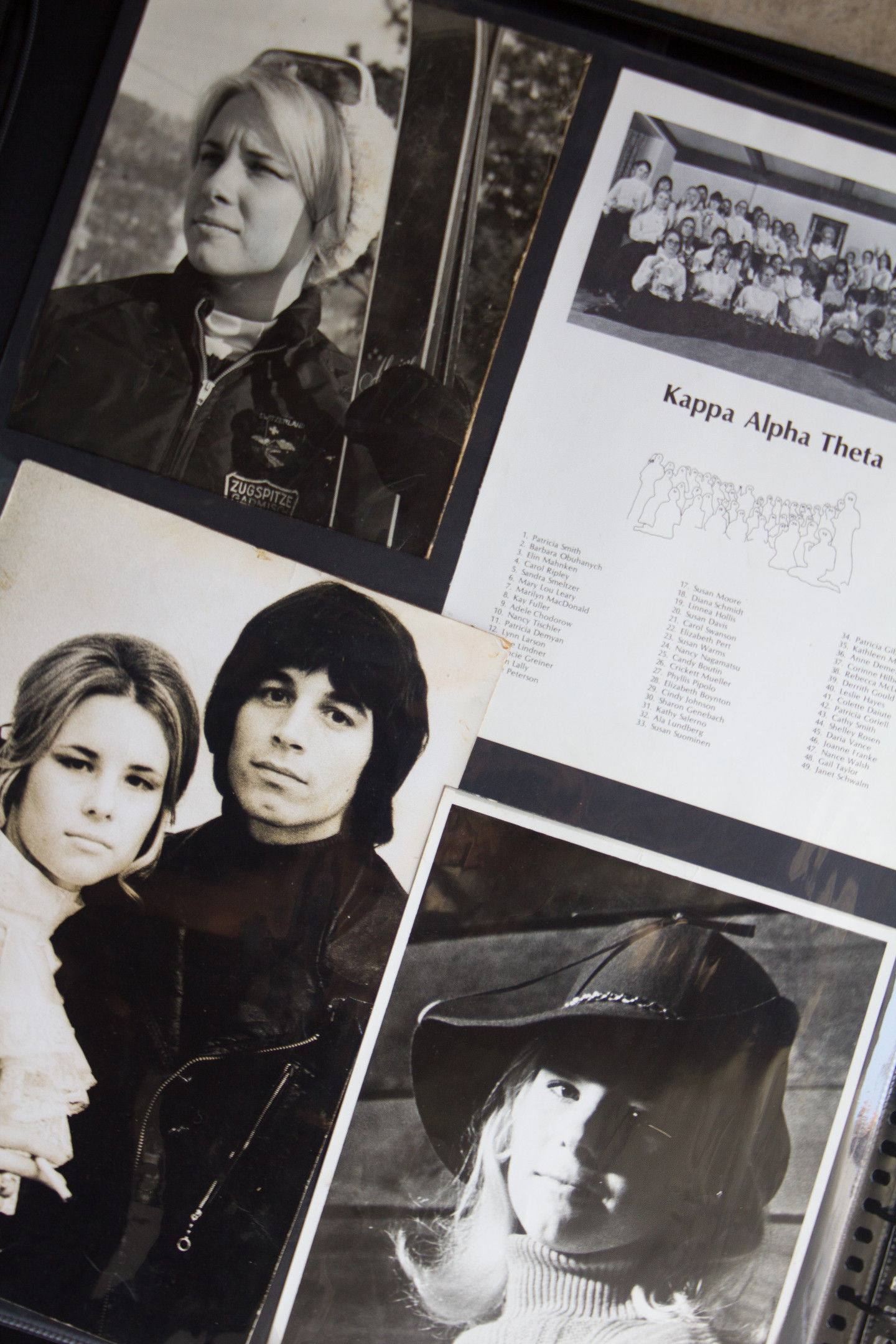

People ask me all the time, or rather they did for a while and do now on occasion, how I’m grieving. Grieving? What is that? I don’t get it. My mother left behind a very tangled legacy that I’m still trying to unravel. It’s as if her life was this fine gold chain, and at some point it got so complicated, so bound up and twisted and knotted, that she grew tired of undoing it all and just let it go. I suppose she assumed (like we all do) that she had more time, more years — even decades — to worry about sorting it all out. But now I’m left sitting up late at night at my desk, a single lamplight shining down as I’m surrounded in the complete black of night, my eyes growing red and blurry as I carefully try to unknot 68 years of someone else’s life. And all along I feel alone and weary and exhausted as I try desperately to work as quickly as I can so that I can rest. But all the while I’m begging my shaking hands to just not break the chain. It is too valuable, even still.

Grief is the strangest creature. It’s like there’s constantly this gray, waxy film covering me. Over time I’ve clawed at my eyes to be able to see the road directly underneath my feet, but the rest of my my body is still covered and sluggish under its weight. I pretend like it’s not there, be frank about my mother’s death and subsequent absence when I’m asked about her. The thing is, it is what it is. And that will never change. Grieving and moving forward and coming to terms may be helpful, but they won’t change the reality that my life goes on with a distinct and painful hole in it. The odd thing is, in a way, being frank about her death is honoring my mom’s wishes. She was a forthright person if there ever existed one, and she would be mortified to think that any of us left here on earth are sitting around boo-hooing and mourning her passing. In fact, the night she died, she talked to my grandmother over the phone and told her, “Now, Ma, don’t you sit in that chair in the corner and cry over me.”

Over the past year I’ve been faced with all sorts of strange circumstances that have reminded me of this — especially when I want to get rid of something she bought for me or the girls. I’ll be standing at a trash can holding a broken baby toy that no one in this house will ever play with again, and I just can’t seem to drop it in. But she bought this for E.V.’s first Christmas. I debate and feel the weight of that waxy grief holding my arms and shoulders down like gravity, and then that part of me that is of her swells up and reminds me exactly of what she’d say: “Seriously, Natalie. It’s a toy. Trash it.” And I do. And then I try to forget that I did because it still hurts, but life has to move forward.

And life does move on, even without my consent. They say firsts after a death are the hardest — the first Christmas, the first birthday, the first anniversary — but what no one mentions is that when your mother passes away while your children are young, there are decades of firsts before me to live through without her — kindergarten, boyfriends, proms, driver’s licenses, graduations, marriages, babies — and while all these things are weighty and lofty by their own merit, her absence will always dampen the experience just a little in my heart. And the worst part is, I’ll never really be free to talk about that feeling of incompleteness, because I won’t want to steal the joy from my daughters’ own experiences with my sadness. The feelings of loss and loneliness will remain in my own internal conversation because it’s not fair to them, and, truthfully, they won’t understand anyway. I try to talk to the girls all the time about Yia Yia, but I know that she’s already a memory to them, one of a fun old lady who wore a trench coat lined with bank teller lollipops. And I have to be okay with the idea that their relationship with her will stop there, because, well, it is what it is.

And then I remember the same is true for me, too. Our relationship is over. It is what it was. And then I think about all the times I hurt her, and I’m angry at myself. I think about all my regrets. Even the stupid ones, like why didn’t I insist on taking a family picture at E.V.’s fourth birthday party, just was a week before she grew ill? Why am I not in the last healthy, happy photo I have of my mother? How infuriating is that missed opportunity? I think about how I lived so much of my life without her in it. Yes, I was young and selfish and unaware, as I suppose everyone is during their early adulthood. But I also always assumed that I’d have at least 20 more years to make up for it. But I don’t. And I have to live with that in the pit of my stomach everyday. And then I think about all the things left unresolved between us, how just a few mature conversations could’ve left both of us with so much closure.

The reality is, I’m still haunted by the way in which my mother passed. It was such a short timeline from diagnosis to death, and yet it felt like the longest stretch of time in my life. It was a time filled with so much sadness and anxiety and anger and confusion and frustration and guilt. I still think of how her face changed over those few weeks. I’ve stared at my own face in the mirror wondering if mine will do the same one day. Will my mouth turn down in a permanent frown like hers? It was eerie to see her with her resting face so inherently sad. I never want to be that sad. And I know she didn’t want to, either. That’s why she gave up. It was all too much, and I get it.

During those few weeks, especially toward the end, I remember driving in my car down a tree-lined street one evening. The sun was setting, so the sky was lit up in a million different colors. I was exhausted and weary and at my wit’s end. I said out loud, “God, heaven has to be real. I really just need it to be.” For the first time in my life, I realized the significance of a place of peace and rest after death. I’ve always thought that going to heaven or hell was the dumbest reason to try to show people the way to God. I mean, we are a people who live in the here and now more than ever, so really who gives a crap about some seemingly imaginary places that might exist one day way down the road after this life? In my opinion, you can’t show-pony or scare someone into knowing Jesus. Truthfully, I don’t get giddy at the notion of being a harp-plucking angel or walking down a street of gold to my mansion the clouds. (Get real, people.) But the idea of a New Earth, where all the weariness of this life is sloughed off, where the waxy film of grief and mourning are melted away so that we can see and run and bask in the sun without worry? Now that, that is something worth believing in enough to change a life. That I can see and that gives me hope. And that’s what I pray for my mother. A redeemed story, a healed body, a happy heart, and a permanent frown replaced with a beaming, glowing smile. Forever and ever amen.